“Stop, drop, shut ’em down, open up shop…”

In the beginning, DMX (X) did not have a fan in me. My young Hip Hop heart was still too busy mourning the then-recent, tragic deaths of 2Pac (1996) and Notorious B.I.G. (1997) to appreciate DMX’s 1998 debut, It’s Dark and Hell is Hot. The black and white music video for “Get at Me Dog”, a performance at New York City’s legendary Tunnel nightclub, was lost on my Detroit eyes. Not to mention I was turned off by a human barking at me from the TV screen. But that all changed when my cousin, who’d once shared my feelings toward X, came over one day and said, “A yo, I changed my mind, and you should too.”My cousin’s eyes looked serious as he stopped my radio, frisbee-tossed the CD inside and forced me to listen. Once the intro track played DMX’s rapid-fire flow matched with the horror-movie beat, I not only became a convinced fan but an awakening emerged inside of me.

“Come on, ma, you know I got a wife…”

DMX became the response I didn’t know I needed to the shiny-suit Hip Hop era. His music represented the streets where I was being raised during the time. “Stop Being Greedy” reflected the neighborhood robbers who stole from the flashy would-be drug dealers, while “Who We Be” gave the reasons for their actions. My friends and I shouted “What’s My Name” at traffic lights as X’s drill-sergeant voice commanded our attention. DMX’s words became images inside my head, and his storytelling rhymes painted pictures more vivid than any Dr. Suess book. He was unafraid to showcase sensitivity on “How’s It Goin’ Down” and a strong sense of vulnerability on “Slippin’”, which offered me an immediate sense of relatability that I seldom could rely on from any artist. My sister and her friends shouted out their names with laughter on “What They Really Want” as X rapped about struggles with celebrity and its temptations. On collaborative records—such as “4,3,2,1” (LL Cool J, Canibus, Red & Meth), “Grand Finale” (Ft Nas and Method Man) and “Money, Cash, H***s” (Jay-Z)—his verses would always outshine the other artists. His energy on records screamed louder than just being a rapper, DMX was a rock star.

“Where’s my guardian angel

Need one, wish I had one…”

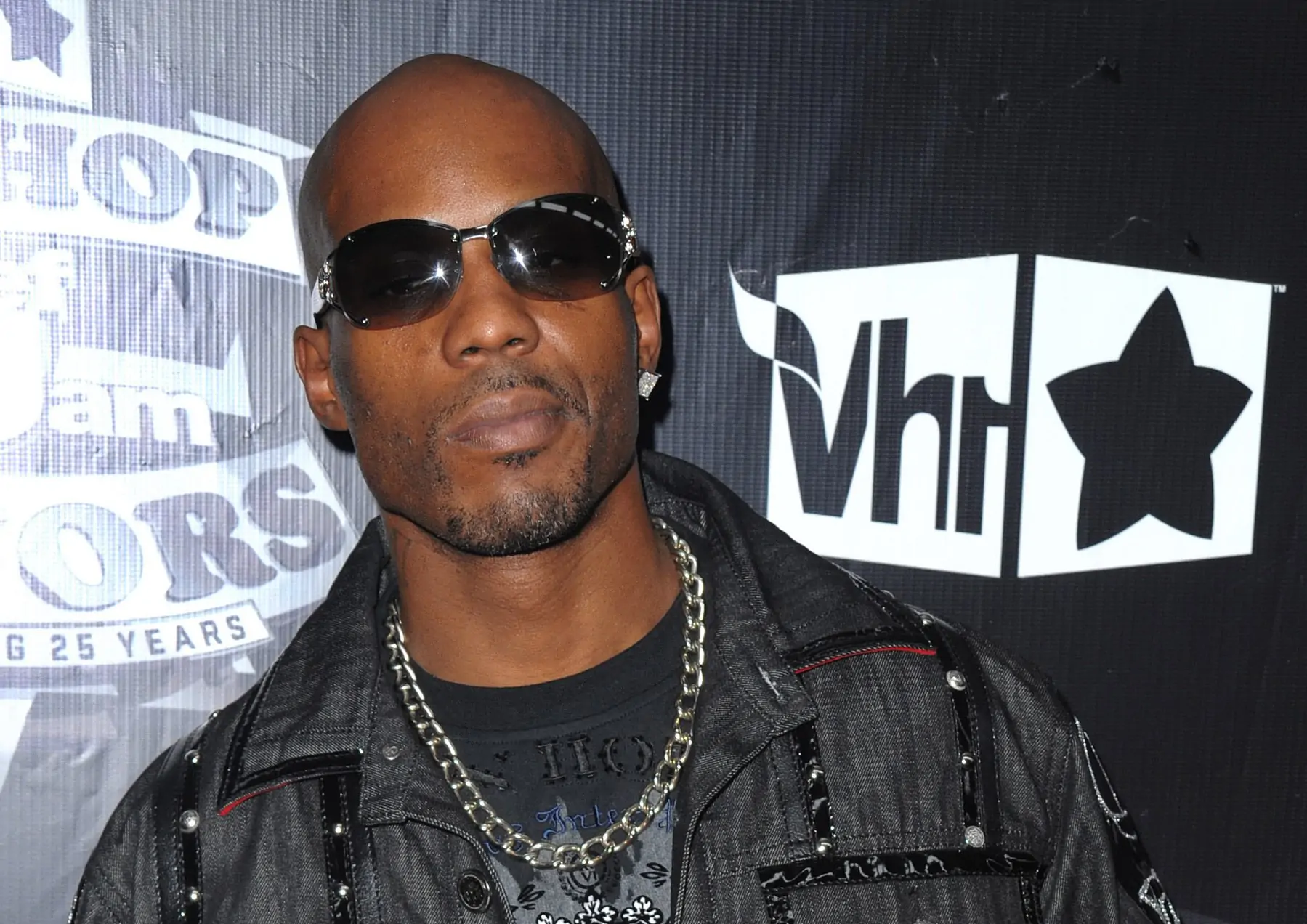

X quickly became my top rapper of the era on a list that contained Nas, Jay-z, and Big Pun, and his Hip Hop /street acclaim crossed over to rock-star status during his Woodstock ‘99 performance. I watched as swarms of white MTV fans hung onto and sang to his every [N-]word. However, unlike some past rappers who reached huge success by conforming to a safe, bubble-gum mass appeal, DMX was an uncompromising slap-in-the-face to white suburban America. He brought the white pop world to the streets and not the reverse. After he starred in the hood classic film Belly as Tommy “Buns” Bundy, X went on to act in Hollywood blockbusters such as Romeo Must Die, Exit Wounds, and Cradle 2 The Grave—all films that took my summer part-time job money. In movies, DMX was one of the greatest actors to play himself. My excitement grew even more when I discovered that his speaking voice was exactly like his rapping voice with the same ebb-and-flow speech pattern, just without a background beat. Whether on screen, on the mic, or on the red carpet, DMX represented the streets where he walked—to a fault.

“They put me in a situation forcin’ me to be a man

When I was just learnin’ to stand without a helping hand…”

Trouble and celebrity seem to go together like syrup and pancakes, so it was no surprise over the years when reports of DMX’s troubles with the law began to outshine his talent. At the time, his multiple legal issues felt like a requirement for authenticity. The keeping-it-real attitude, indulged by me and many Gen X/Xennial Hip Hop fans, seemed on-brand for a DMX-type while others thought he was just another Black celeb purposely blowing a rare opportunity. DMX didn’t shy away from his demons. In fact, he would often address his personal battles very publicly when at the end of every show when he would conclude the performance in prayer while covered in sweat and tears.

As the years passed, I, like many, developed a humped-shoulders attitude towards any wild DMX story. Sometimes his interview responses were comical. His reality show appearances made me cringe. I began to realize that my viewing DMX as a god-like figure in the past made it especially hard to watch his humanity unfold on screen. Through the years, his pain was entertainment to me and millions of other fans who often don’t consider the effects on an artist who puts their darkest emotions on public display. When fans rant about loving the old Mary J Blige or needing to hear the Reasonable Doubt Jay-Z, they selfishly fail to consider the importance of the artists’ growth away from a once unhealthy or tragic life.

“The heartbroken mothers, it happens, too often…”

DMX will always be a bright voice for those from the dark slums. The Black figure that America drags through the mud as a youth, praises them for growing through the soil, then lacks any sympathy for their being traumatized by dirt. His music raised millions who felt lost in a world. His attitude was authentic and unapologetic. His songs were timeless. He is an iconic figure representing the Black American struggle of rags-to-riches with no manual of what to do with that newfound fame. X was shamelessly vulnerable as an artist whose most traumatic experiences of inner-city Black life connected him with those from similar backgrounds and entertained others fascinated with Black trauma. Dark Man X is a legend who provided the streets with a soundtrack, a passion for the culture, and a voice for the forgotten.