Streetwear style is 50 years in the game, and Black women are still pushing back against erasure.

When it comes to Black women in fashion, there’s always a story to tell. The story started in Africa, where hair styles, jewelry, and fabric conveyed a variety of messages about social status, family clans, and mourning or celebration. That story shifted on American shores and became something more complex, something that through the years has been political and rooted in either respectability or resistance.

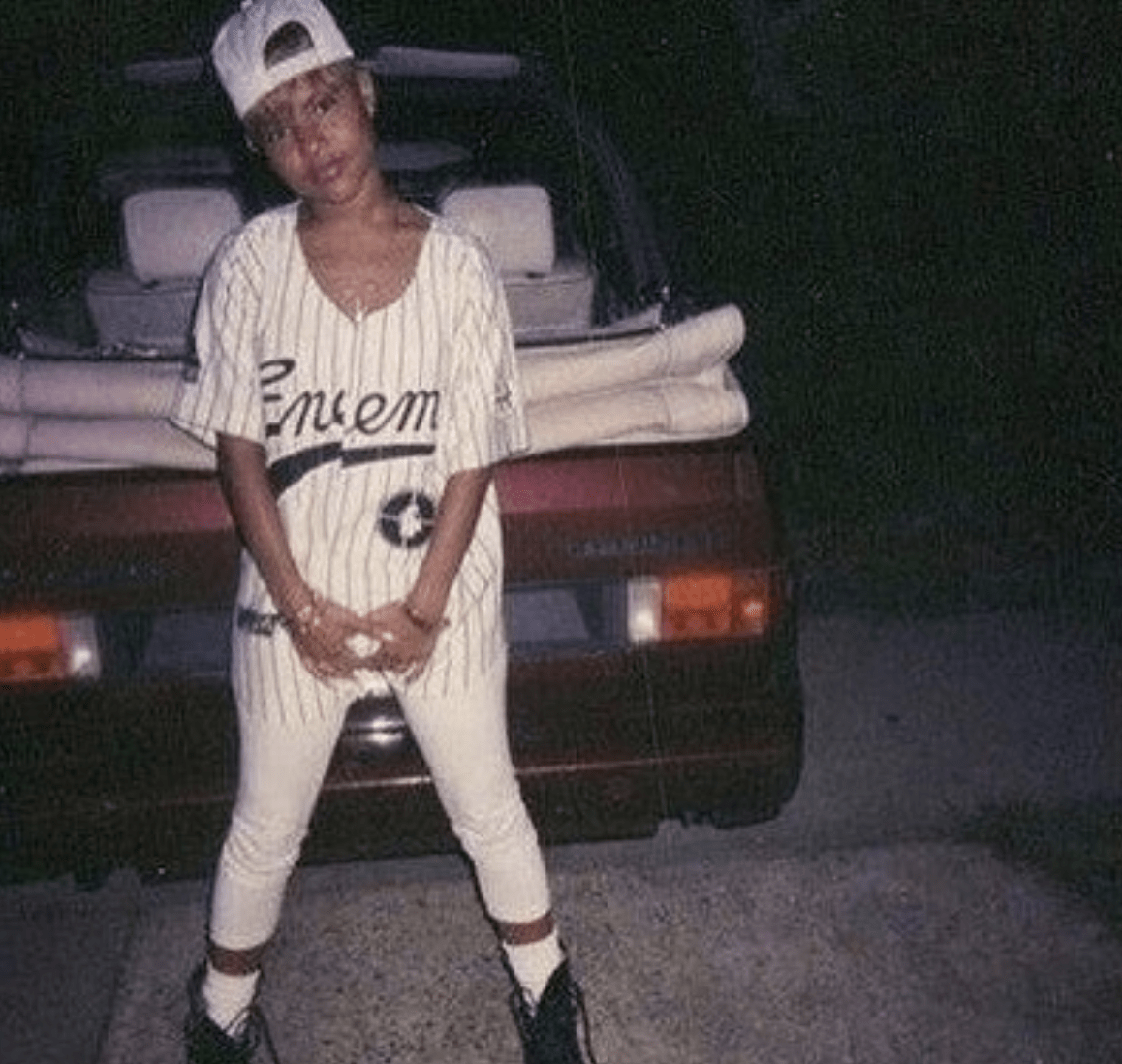

My style story starts in New York City. I grew up in East Harlem and The Bronx in the 80s and 90s, when NYC looked like a warzone littered with rubble from intentionally burned down buildings. Despite that ugliness, this was also the time when hip-hop was manifesting (and had been since the early 70s), and the youth were exploring their identities through music, dance, and style. I’d already inherited a love of leopard print and red lips from my mother and her mother, and while I was too young to wear either, I noticed my foremothers and the women in the neighborhood. I was fascinated by the different ways they styled themselves. There was an abundance of bucket hats, tracksuits, intricate nails, finger waves, biker shorts, custom clothing, and the rise of sneaker culture. Today, that’s called streetwear. Back then, it was just how we dressed before outsiders scrambled to label it. First it was “urban”, and then “streetwear” began to emerge as a descriptor in the early aughts when hype beast culture started to water down the culture.

Today, streetwear is global and more popular than ever. Even luxury brands who once shunned anything related to hip-hop style have adopted its staples.

But at what cost?

What we’ve seen over the years is that Black culture is reviled, but that’s only until it gets commodified and promoted as someone else’s creation—often with Black women creators being the first to be erased. That is what happened in streetwear. For decades, Black women were missing from ad campaigns, music videos, magazines, and TV shows, and credit for our style contributions were misappropriated (think “boxer braids” or name plates).

However, with the advent of social media, “representation” is now cool and we are starting to reappear. Brands have been partnering with Black influencers for “drops”, women like Misa Hylton, Kiki Kitty, and April Walker, who’ve created some of the most iconic looks in streetwear fashion history. But inclusion is often fleeting unless we are persistent about controlling our narratives.

As a millennial, I consider myself second generation hip-hop. We’re the last generation to experience art, style, and culture before the internet and before people could just pull up quick photos for style inspiration—when more thought and effort needed to be put into looks and obtaining clothing and accessories. I reached out to other Black women millennials to discuss how we historically entered the world of style through streetwear and most importantly, how we can avoid erasure moving forward.

This is a love letter to the co-engineers of streetwear, the architects of style. If no one else sees you, I do, because I live it too.

History, Influence, and Impact

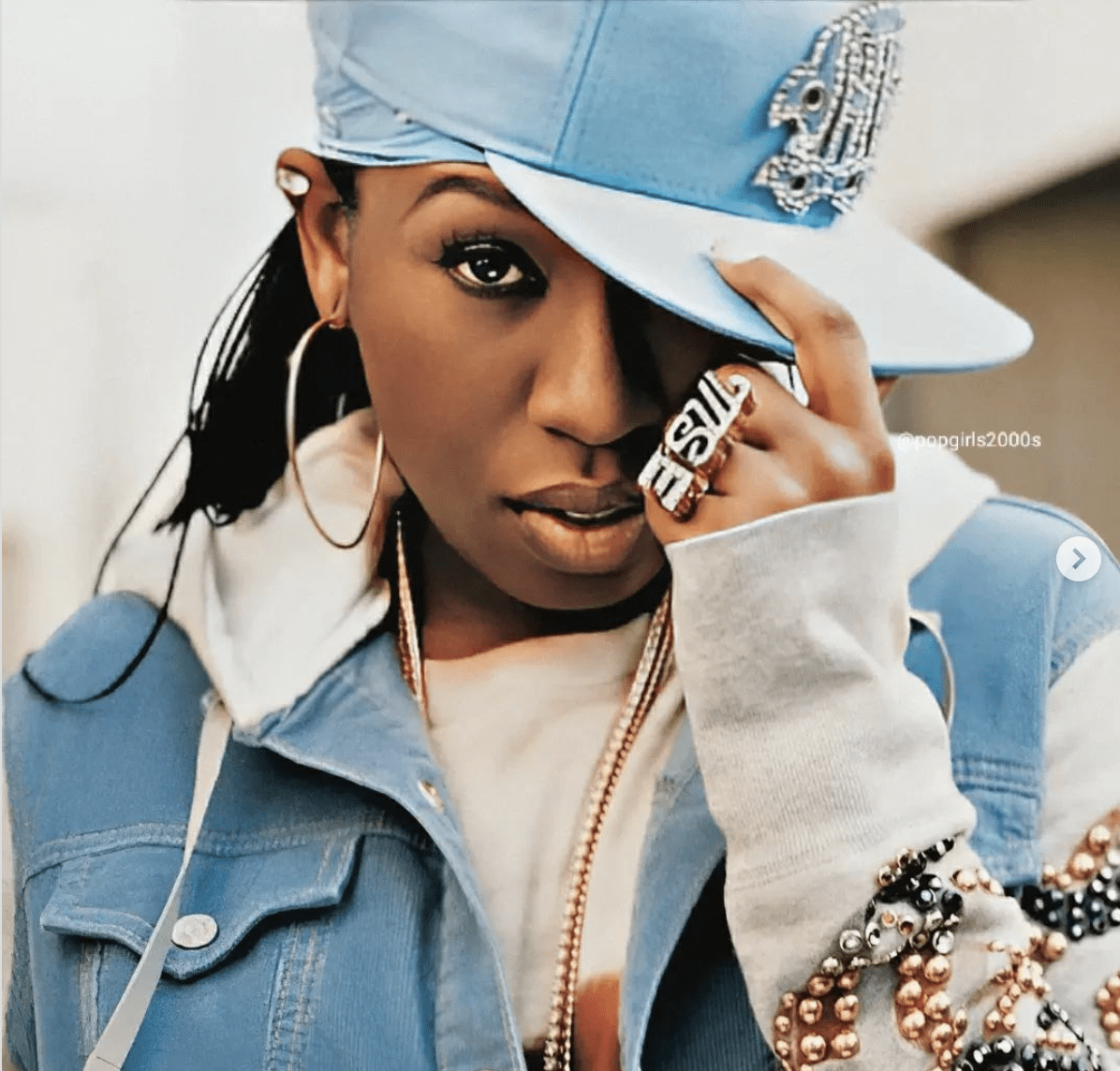

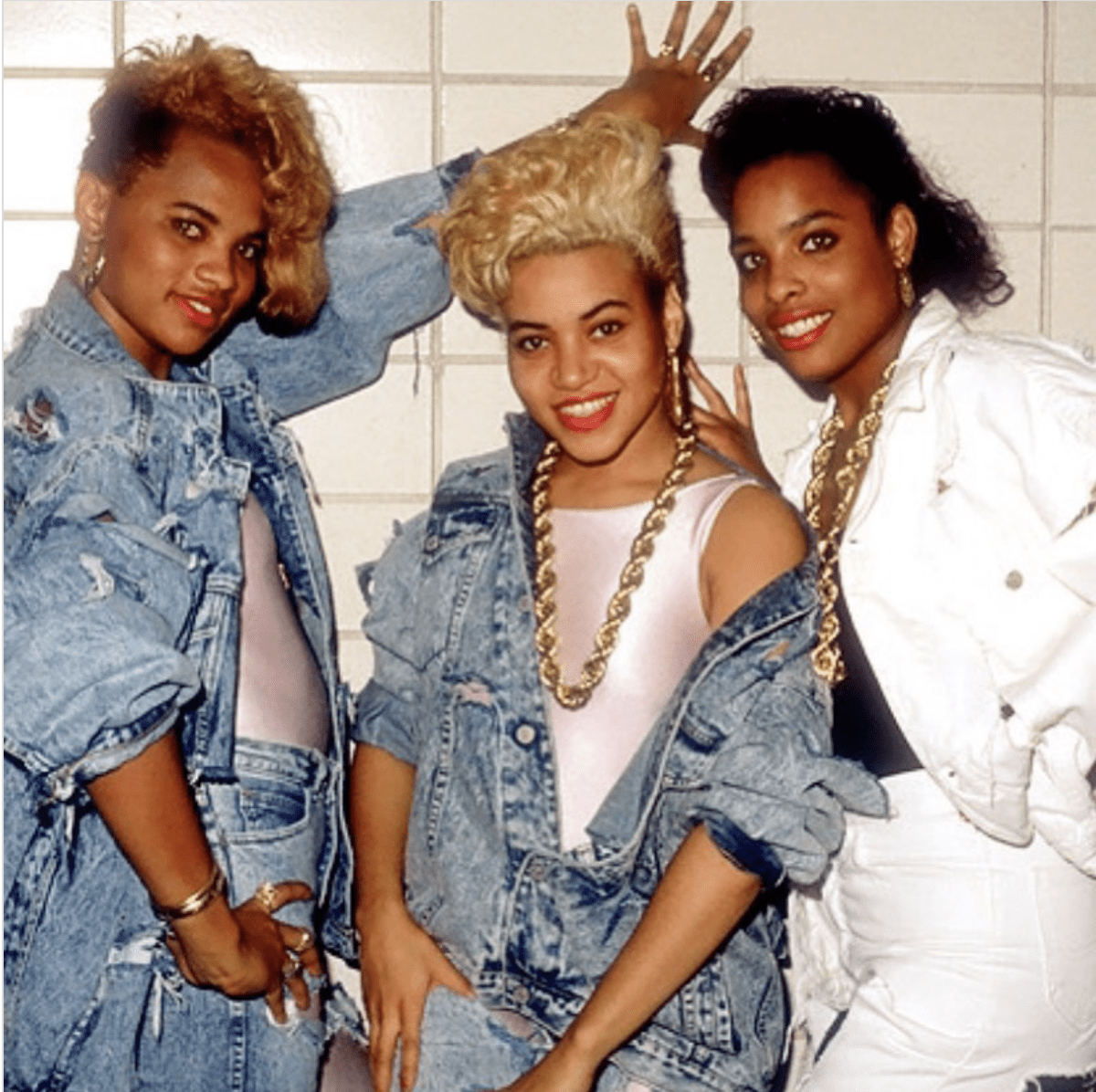

Black women have always existed in a unique space on the spectrum between respectability and resistance. Early women in hip-hop style often wore oversized clothes and sported a tomboy aesthetic, but accents and adornments like nails, earrings, hair styles—and, later, more form fitting clothes—underscored their femininity in a way that didn’t hyper-sexualize them. Later on, women like Foxy Brown and Lil’ Kim began to embrace hypersexuality and introduced the possibility of a high fashion mash up with hip-hop. Both were muses for designers like John Galliano for Christian Dior and David La Chapelle for Louis Vuitton, respectively.

But self-expression isn’t free. Because no matter how you dress, when you’re a Black woman, people are going to have something to say about the way you present yourself.

“I didn’t realize how much respectability politics was involved,” explains fashion executive Shirae Ravenell, “until my mom wanted to make sure I looked a certain way to get a certain type of job after I graduated. I suppressed what I really wanted to look like until I started making a certain amount of money to where I didn’t have to play that game anymore.”

Shirae, who grew up in Brooklyn and then Jersey City, New Jersey, has over 15 years in fashion as a director of sourcing and in other capacities at brands like Coach, Bandier, Alexander Wang, and more. In our chat, we bonded over a lot of things but especially our mutual love of nails and how our mothers wouldn’t let us rock outlandish nails (read too long and too colorful) outside of our homes.

“Me and my best friend would go to the 99-cent store after school and get a pack of nails,” she explains. “I would put them on, on Friday, so I could live my SWV life. It was from 4 o’clock on Friday until Sunday—until the last minute, like at 8—and my mother would be looking at me like you already know, take them off.”

Ravenell describes her aesthetic growing up as feminine and says she gravitated toward Baby Phat and Sergio Velente jeans because they “made her look like she had a booty.”

“For me, [streetwear] was learning who I was via music, and it’s a symbiotic relationship between the two. There is no streetwear without music and Black culture. And so much of needing to have the North Carolina Jersey dress that Mya wore, and needing to have a Coogi dress and fresh Air Forces at the basketball game during the summertime, these were specific things that called for specific outfits. Even though we didn’t have social media, we all knew. We were all on code.”

Imagine Shirae’s surprise when one of her first internships after college led her to meeting Kimora Lee Simmons, one of her favorite icons in fashion. It was at a mom-and-pop garment company where she worked on their Louis Vuitton account. Baby Phat was also one of their clients and suddenly they realized the need for diversity.

“They invited me to this meeting,” she recounts. “I was 22 so, I was like, ‘Oh my god, Baby Phat!’ I had no idea that they were about to use my Black ass to show up in front of Kimora as the token. So, Kimora Lee Simmons sees me and goes, ‘This girl doesn’t even work on my account. Did you find the only Black girl in your office to talk to me?’”

That chance encounter led to Shirae getting first and second row spots at Baby Phat fashion shows. As she advanced her career, she was also privy to the types of brand deals being made that most of us only get to see on the front end, and she learned a lot about how often the faces of products don’t have a say in the design and marketing decisions.

“We get so few opportunities to do things like this,” she says, “that most folks give up their chance to really be impactful and to have a seat at the table. Oftentimes, it’s a design team that does everything, and they’re just going through the normal process of their regular life-cycle calendar. They’ll take your feedback on a color way or things like that, but they’re not making any major changes to designs they already have. You’re not going to get that unless you’re collabing with an actual individual designer. So, what happens is, a lot of their stuff just looks the same, especially if you’re dealing with a retailer that has a large supply chain.”

What Shirae was getting at is that if people are starting to look the same, then it’s not all in your head. That is why creativity, maintaining archives, and autonomy are important.

What Goes Around Comes Around, but Keep the Discussion Going

So, why are we even talking about this again?

Danielle Kwateng, who is currently executive editor at Teen Vogue, cites Hip-Hop’s 50th anniversary as one of the reasons, aside from social media, why we are even having this ongoing discussion.

“There’s going to be so many more conversations this year, especially with hip-hop turning 50, around the culture,” she explains. “We’re going to be talking about who were the founding fathers or founding mothers, the evolution of hip-hop from just a thing to know to the global genre, lifestyle, culture beast that it is. I love the conversation about women in fashion and streetwear, specifically, because there’s been a lot of erasure of women in hip-hop. We knew about Dapper Dan, Damon John, and Sean John back in the day, but very little is talked about April Walker or Bevy Smith or these women that were a part of that time, that dress, and that expression when it comes to women showing up in Black music culture. Streetwear is essentially a reflection of Black and brown people in urban spaces, and that’s why I’m marrying it with hip-hop because it just feels so natural.”

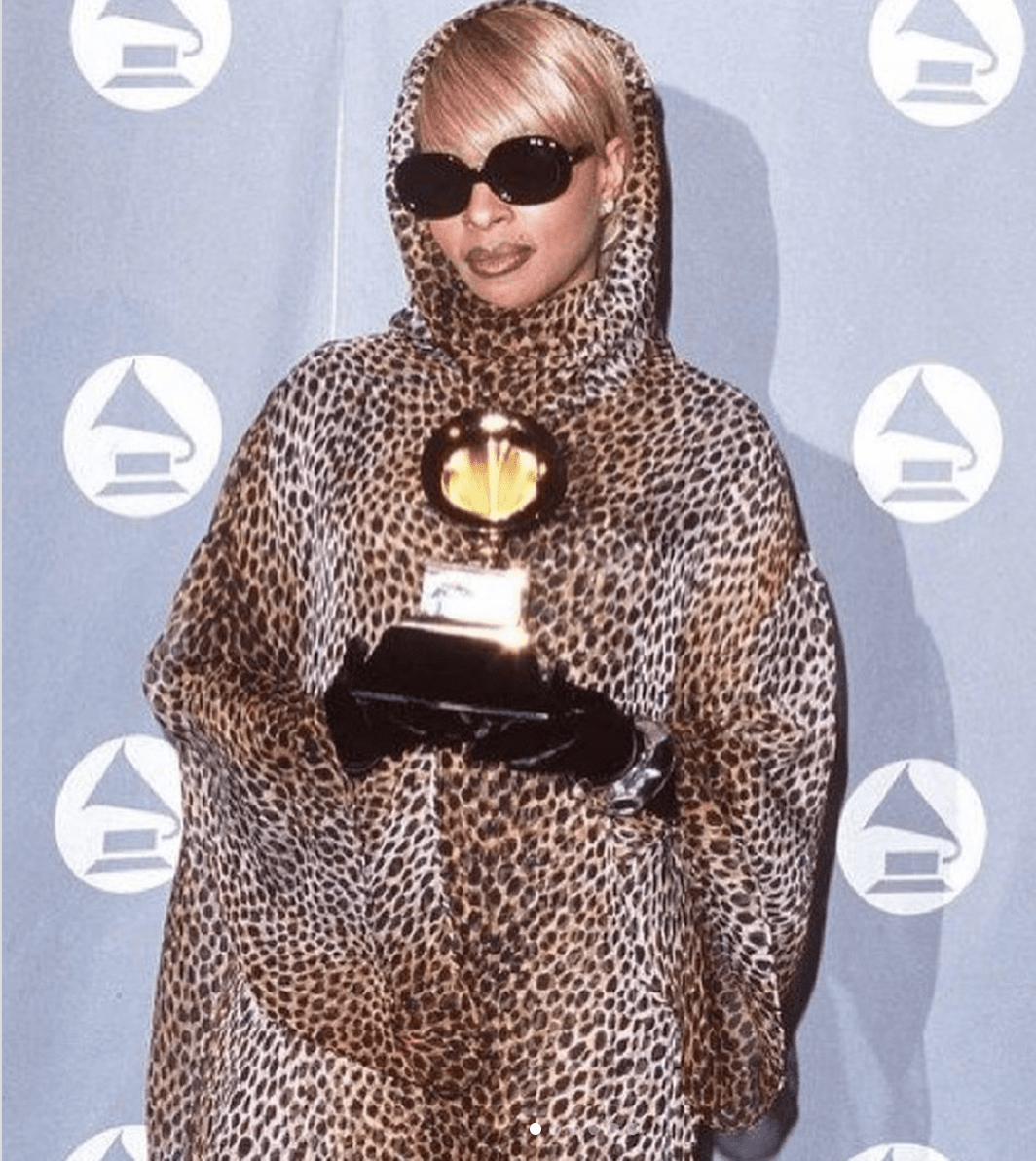

All of the women I spoke to cited magazines, music videos, and even fictional characters like Moesha or Zaria from The Parent Hood in addition to Mary J Blige and TLC as women who inspired looks from braids to apparel.

Danielle, who grew up in South Florida, also nods to the rise of Slip-N-Slide records and other southern influences from Atlanta, like TI and Jeezy.

“A lot of that southern influence was part of Florida’s DNA and culture, but my first moment was probably through sneakers. I don’t know if anyone else was like this, but we loved Reebok Classics in Florida.”

Kwateng also talked about saving money to buy her first pair of Nike Cortez because she had a lot of Latino friends who were into Cortez’s. In New York it was either Jordans, Air Max’s or 5411’s (the latter of which I begged my mother to buy me). But as style is cyclical, it’s interesting how many of these silhouettes have made a comeback.

“There’s been a resurgence of ’90s and 2000’s style,” she says. “There’s something about that period of time in the culture that’s raw and sweet that these girls are loving. I think of Ice Spice or even Pink Pantheress. The early ’90s and 2000’s was a time of vast expressions on both ends. You had the girly, bubbly clothing and expression but also raw, edgier street styles. Think Spice Girls but then Mary J Blige, Missy, and on the other end, Lil’ Kim.”

Maintaining Ownership

When I asked each woman why Black women have been so easily erased from streetwear, one of the most common answers was that we’re often taught to play small—even when it comes to things we helped create. We’re taught to be supportive and to take hits for the team, which makes us the mules. But now that it’s easier for us to have our own platforms, we must focus on archiving what’s ours, making shrewd business decisions, and supporting each other where we can.

I was digitally introduced to a woman named Jeneene Bailey-Allen who grew up in Philadelphia in an area called Germantown, which was close to what natives would know as Chestnut Hill.

“It wasn’t hood but it wasn’t suburban either,” says Bailey-Allen. “So, I grew up there, raised by my grandma, and I think where fashion came into play was seeing her and her sisters when they would get dressed up to go to different events or to the casino. But then also my mom used to be heavily into arts and crafts. That’s where the seed was planted. I was just born liking fashion. I would get the magazines, and if I missed an issue, I really wanted I would beg for $6 so I could get it sent to me—tear out the pages for inspiration. I had a whole wall in my room.”

Jeneene, who is currently the Fashion Immersion Program Coordinator at Thomas Jefferson University and the founder of ASGNMT, says Tommy Hilfiger, Nautica, Polo and Girbaud were the major brands of interest for her growing up. She describes her personal style then as Tomboy, or just being herself.

“I remember when prom time came,” she says, “I had to learn how to walk in heels because my mom was like, ‘You can’t wear sneakers to the prom, Jeneene!’ So, I had a textbook on my head walking around the house in heels—like it was a permit to learn how to walk. And I was like, ‘I’m only keeping this dress on for pictures and after that, I’m changing’, and that’s literally what I did. I changed into something more comfortable that included sneakers.”

Jeneene launched ASGNMT last year. It’s an e-marketplace focused on building and representing the cultural presence and contributions of Black and brown women in streetwear.

“It’s geared toward Black and brown women but not limited to Black and brown,” she explains. “It’s the BIPOC community, but women ultimately, especially those who are in these male-dominated industries. You see at these different sneaker events and conferences that they are almost always geared toward Asian and Caucasian men, but I created ASGNMT because there are women—some are their partners—that they bring into those spaces who are interested in those things as well.”

Jeneene is working on building ASGNMT into a marketplace that brings together women-owned brands in this space and celebrates one year since launching on 4/20.

“Ultimately, I want a space for ASGNMT that houses different women-owned brands that people can come and visit. So, a global brand of sneakers and streetwear but all in one spot, almost like a Kith but for women…that’s the assignment.”

How We’re Moving Forward

Ownership, not playing small, generating new ideas, not falling into the social media trap of copying people because what they did got clicks, well-researched business moves, and keeping the discussion going are how we fight back the forces that try to erase us.

Jeneene sums up the why perfectly: “We’re the blueprint. We’re The reason why these fashions are here and evolving, so we have to stop letting that get washed away. Let’s give us our flowers while we’re here and give credit where credit is due.”